Table of contents

1. The Kahun Papyrus (1800 BC)

2. Trota of Salerno (12th Century)

3. The vaginal speculum

4. 18th and 19th centuries

5. 20th and 21st centuries

Written by Izzie Price

Illustrated by Valko Slavov

Fascinating; illuminating; clarifying; surprising; frustrating; horrifying – all words you could use to describe the foggy, confusing (and, too often, hidden, tucked away or written out altogether) journey that is the history of vaginal health.

We’d always support anyone who wants to take a deep dive into the vagina and the developments in vaginal health over the centuries. But we know it’s not often the easiest ride, and we understand if you’d prefer not to keep reminding yourself that, for far too long, the vagina was (and often still is) a taboo subject (and word).

Take the ancient Greek physician Aretaeus, for example. He thought the womb wandered around the body like an “animal within an animal”, bumping into the spleen or liver and subsequently causing illness [Kahun Papyrus: Nunn, J. F. (1996). Ancient Egyptian Medicine]. (We know; we know.) Meanwhile, Galen – considered, at the time, to be the foremost medical researcher of the Roman Empire – disagreed with the ‘wandering uterus’ theory; but that wasn’t a win for people with vaginas. Galen, instead, saw the vagina as an inside-out penis [Galen’s theories: King, H. (1998). Hippocrates’ Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece]. In other words, he thought a woman was a lesser version of a man (shock!).

It doesn’t stop there. For uterine prolapse, healers used pessaries – wool suppositories soaked in herbs or pomegranates soaked in wine. To manage heavy menstruation, Hippocratic healers inserted pessaries made of wool soaked in vinegar and myrtle, thought to regulate bleeding. They also recommended dietary changes, like avoiding red meat, to “cool” the body—a reflection of humoral theory [Totelin, 2009].

Plus; Greek texts often blamed women’s illnesses on moral failings, perpetuating stigma.

Yep; it’s a wild ride journeying into the forays of vaginal health history, and there are some unpleasant (although, regrettably, unsurprising) revelations along the way. But here’s why we’re doing it anyway: Firstly, it’s not all bad. Some of it’s seriously interesting; and even encouraging. And secondly, like we’re always saying, knowledge is power. It’s only by understanding how we got to where we are today – with medical gaslighting, medical misogyny and gender-based healthcare discrimination still running rife – that we can tackle the current state of things. In other words: We look to the past to make change for the future.

So, with that in mind, let’s take a deep dive into the history of vaginal health. We can’t revisit every single historical moment, obviously; but we’ve zeroed in on some highlights…

The Kahun Papyrus (1800 BC)

This is the oldest known medical papyrus (!), found in Egypt in 1889. It focuses on women’s health and hones in on issues like gynaecological conditions, fertility, pregnancy and contraception.

It’s neatly split into 34 sections, with each section focusing on a specific condition and detailing diagnoses and treatment. The treatments aren’t what we’d often be used to today; for a start, they’re non-surgical. For example, treatments included topical applications, like honey mixed with natron (a natural salt); and to treat uterine pain, the papyrus recommended a paste of dates and rush nuts applied vaginally – thought to soothe inflammation. Fumigation was common, too; specifically, burning myrrh and directing the smoke into the vagina with the aim of ‘purifying’ it. These remedies were often administered by female healers, who held respected roles in European society; they’d blend empirical knowledge with spiritual rituals [Nunn, 1996].

Contraception, too, perhaps isn’t what we’d go for today in favour of condoms or the pill; options in the Kahun Papyrus include crocodile dung, 45ml of honey and sour milk. We’d opt for a modern-day pregnancy test, too, over placing an onion bulb in the flesh (presumably of the vaginal canal) and determining a positive outcome based on whether the odour reaches the mouth...

But, regardless; we’re always keen to hear about anything that suggests people have been concerned with gynaecological health for a seriously long time; and the Kahun Papyrus certainly does that.

Trota of Salerno (12th Century)

Trota of Salerno lived in the 12th century [Trotula: Green, M. H. (2001). The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine]; she was an Italian doctor and is often considered the world’s first gynaecologist. Very cool.

She was a physician and a professor at the Medical School in Salerno, Italy; and she distinguished herself by focusing on women’s health. She became an expert at diagnosing conditions unique to people with vaginas, like complications in pregnancy; and she encouraged the use of opiates during labour. We really, really love this, because it meant she was going against the Christian belief that, at the time, said women should go through as much suffering as possible during childbirth as punishment for Eve’s sin.

Her text On the Conditions of Women detailed remedies like rose oil pessaries for menstrual pain and postpartum baths with chamomile. In her words: “For pain of the womb, take oil of roses and anoint the vagina.” She also advised wrapping the abdomen in warmed linen post-delivery to support healing, a practical approach that resonated with midwives across Europe [Green, 2001].

Trota was seriously influential and her work informed medicine surrounding women’s health for centuries after her death, with doctors throughout the medieval world looking to her reference work for treatment solutions for female patients. One of her books was written with a view to educating male doctors about the female body, and offered information about periods and childbirth, as well as generalised medical issues.

We should add that, during the Renaissance period, doubts started to be expressed by some scholars regarding Trota’s gender; and even her existence. Some suggested she was a man; some, that she was fictional altogether. Today, scholars do believe she existed – but there is ongoing research to determine whether Trota’s work was all hers, or whether it was compiled from multiple authors.

Stay tuned; but for now, raise a glass to Trota.

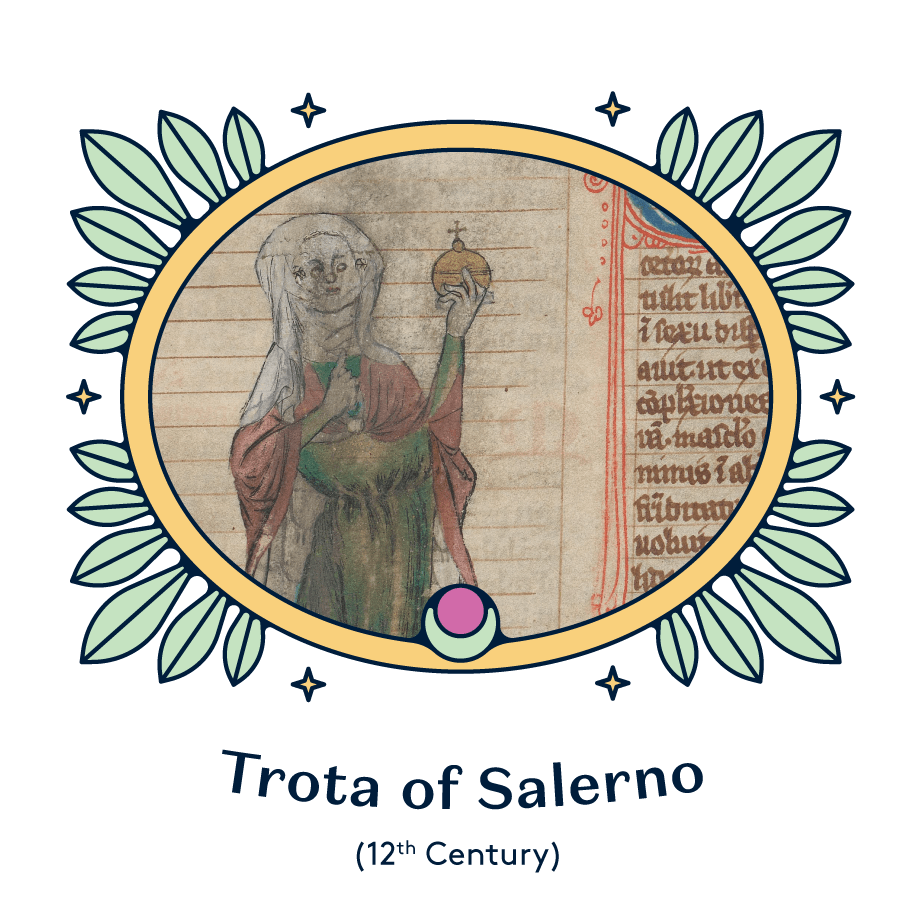

The vaginal speculum

There are no clearer examples of the nastier side of vaginal history than the speculum. It’s thought that the ancient Greek rectal dilator was originally in the form of two spoons; one in each hand; and it’s also thought that a small vaginal speculum was found in the ruins of ancient Pompeii. With the latter, closed ‘blades’ are inserted into the vagina and dilated using a screw mechanism. The blades sit at right angles to the mechanism itself, allowing an easier view straight into the vaginal passage.

This design barely changed for centuries.

Until the 19th century, many physicians worried that using the speculum to diagnose gynaecological conditions might tear the hymen, thus resulting in a loss of virginity. This is, to say the least, nonsense – and yet it was a myth that persisted until at least 2022, with women in the UK being denied medical treatment on the basis that they hadn’t lost their virginity. Just goes to show why we need to take a good, long look at history and debunk damaging, centuries-old myths that still impact our healthcare today.

But back to the speculum. In the 19th century, due to the ‘Contagious Diseases Acts’, women suspected of being sex workers were forced to undergo an internal examination with the speculum; these often weren’t cleaned, were inserted incorrectly, and caused women to pass out from the pain. Social reformer Josephine Butler then started a grassroots campaign against the Acts (as she wrote: ‘Under the present Acts, a man whose infamous proposals have been rejected by a girl, may inform the police against her, and on his evidence the girl may be subjected to examination and ruined’); the Acts were repealed in 1886 but remained on the statute books in British colonies for a long time.

The speculum continued in much the same design for centuries; most were made from metal, which must have been pretty excruciating – to say the least. Then, along came Dr James Marion Sims, who invented the Sims speculum (still used for vaginal surgery today) which was able to slide around the vaginal wall, offering multiple viewpoints. From 1845-1849, Sims developed his techniques by experimenting on enslaved Black women, performing experimental surgery to see if he could repair their vaginal fistulas.

These experiments were performed without anaesthesia, despite the fact it was readily available. It’s since been suggested that Sims left a horrifying legacy behind him when it comes to women’s health; particularly for women of colour.

18th and 19th centuries

We could easily spend endless hours delving into the slightest development in women’s health across the centuries; but we’ll start speeding things up now, or else we’ll be writing a 20,000-word thesis instead of a Vitals post.

By the end of the 18th century, medical professionals were starting to understand the womb’s anatomy (not a moment too soon…) and the bodily changes that people with vaginas go through during childbirth. The introduction of forceps in childbirth took place at this time; and formal training in obstetrics for surgeons had been introduced. We should add, though, that the history of midwifery isn’t all good, and not just because of misogyny; in the 17th century, some African women were enslaved to train and serve as midwives.

In the 19th century, the development of obstetrics began to stagnate, which is generally understood to be because the medical community rejected it as a field; The College of Physicians and Surgeons, for example, considered delivering babies ‘ungentlemanly’ work and refused to engage with childbirth – and if it wasn’t ‘gentlemanly’, it wasn’t worth anyone’s time, apparently.

Midwifery and obstetrics weren’t respected as professions – they were barely acknowledged – and consequently, it was pretty much impossible to pursue education in midwifery. Things changed towards the late 19th century, though, with the delivery of babies finally becoming a respected area for doctors to specialise in and the development of midwifery as a certification based on competence in European countries.

By the end of the 19th century, childbirth was still underdeveloped compared to other medical specialities (again – shock!) but around this time, there were major advancements in anaesthesia – which paved the way for the Caesarean section.

20th and 21st centuries

We’ll end with some more recent highlights to bring us up to the present day:

- The fight for birth control: At long last, people with vaginas were able to access contraception thanks to figures like Margaret Sanger – who founded the American Birth Control League in 1921 and the National Committee on Federal Legislation for Birth Control in 1929, the latter of which lobbied Congress for legislation that would finally let doctors prescribe birth control – advocating for women’s rights. It’s certainly not a spotless history, though; the birth control pill was developed with eugenic ideals. Some eugenicists believed it could be a useful tool for curbing procreation among the ‘weak’ and Sanger tried to ally her cause with this movement.

- The Women’s Health Movement: Yep, this was an actual movement! It developed during the 1960s and 1970s, aiming to improve healthcare for women everywhere. Essentially, the movement was a surge in activism and a political force to be reckoned with. It led to women gaining more control over their reproductive rights – campaigning to have more autonomy over childbirth, for example – and the movement’s efforts in gender-based research mean that, today, women are no longer automatically excluded from early drug trials.

- Advances in reproductive technology: From egg freezing to IVF, modern technology has given women what they campaigned, argued and battled for for centuries: Options. Take the biotechnology company Gameto, for example, which offers a range of services from egg freezing to IVF, to helping with ovarian disease and menopause symptoms. Whether it’s family planning or overcoming infertility, women can now make informed choices and pursue alternative routes where needed.

- Focus on preventative care: Nowadays, regular checkups, pap smears and HPV vaccines are seen as essential for people with vaginas and highly encouraged by healthcare professionals at all levels; because now (at last!), we know how crucially important these preventative measures are for the early detection and prevention of gynaecological issues and, possibly, cancers.

So, there you have it! A whistle stop tour of the history of vaginal health (and, no doubt, your emotions, too; given the juxtaposition between some people fighting for women’s healthcare rights while others did their best to deny such rights existed). We couldn’t cover everything in this one post, obviously – but hopefully, we’ve given some indication that the history of vaginal health isn’t always made up of men pushing women’s healthcare to the bottom of the priority list (or off the list entirely). In fact, some of those historical stories are pretty encouraging; and should add some fire to our bellies when it comes to doing our bit to continue campaigning for women’s health to be taken seriously.

And that spirit of innovation and empowerment continues. As we look to the future, building on centuries of (often hard-won) progress, new tools are emerging that put more knowledge and control directly into the hands of individuals. At Daye, we're proud to be part of this ongoing evolution with innovations like the Daye Diagnostic Tampon. By enabling convenient at-home screening for common vaginal infections and disruptions to the microbiome, it represents a modern step towards the personalised, proactive, and accessible vaginal healthcare that generations have strived for. It’s about taking the power of understanding your own body, a theme so vital throughout history, and making it a tangible reality for today.

Relevant Products