Illustrated by Erin Rommel

Chances are you’ve heard the rumours surrounding the contraceptive pill, but myths and sensationalist information can leave us even more confused about our bodies and reproductive health.

For many, the contraceptive pill is the most convenient and accessible method of contraception. In fact, it’s the most popular contraceptive for women in England and the most reviewed method of contraception on The Lowdown, the world’s first review platform for contraceptives.

The pill is far from perfect (no contraceptive—or medication, for that matter—is infallible), and there is still a huge gap in research on both short and long-term side effects, but scaremongering and demonising a contraceptive that many people rely on doesn’t help anyone.

To put your mind at ease, we addressed some of the most common misconceptions about the contraceptive pill and debunked the myths.

Myth: the pill makes you gain weight

Stories of women putting on weight while on the pill are so widespread that people are quick to ignore the science—we can blame societal fatphobia and diet culture for that.

Rest assured, research has found no evidence to suggest that the pill causes weight gain. A 2014 analysis of 49 separate trials, published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, concluded that oral contraceptives are not linked to weight gain. That same year, another study, published in the Journal of Women’s Health, found that use of the pill is not associated with weight gain or changes in fat composition.

The majority (44%) of reviewers of the pill at The Lowdown report that it has caused “no change” to their weight, 17% “can't tell”, and 35% think it has caused them to gain weight. “This is much lower than I expected before I set it up, and it's not coming out in women's comments really either,” says Alice Pelton, The Lowdown's founder. “But it's very difficult to track and attribute.”

The myth that the pill causes weight gain most likely stems from the fact that the earliest versions of the contraceptive pill (which predate the moon landing, FYI) contained higher doses of oestrogen, which can affect fat mass.

Modern formulations of the pill don’t contain as much oestrogen, and any weight fluctuation is due to water retention. On top of that, other forms of contraception (especially progestin-only contraceptives) do have more convincing links to weight gain, which could cause confusion when it comes to the pill.

Although anecdotally women may experience minor weight fluctuations while on the pill, these are typically related to other lifestyle factors. And most importantly: everybody is different! We each have our body composition, and our weight is affected by so many things—from diet, exercise, age, stress and health conditions.

Myth: skipping the pill-free week is bad

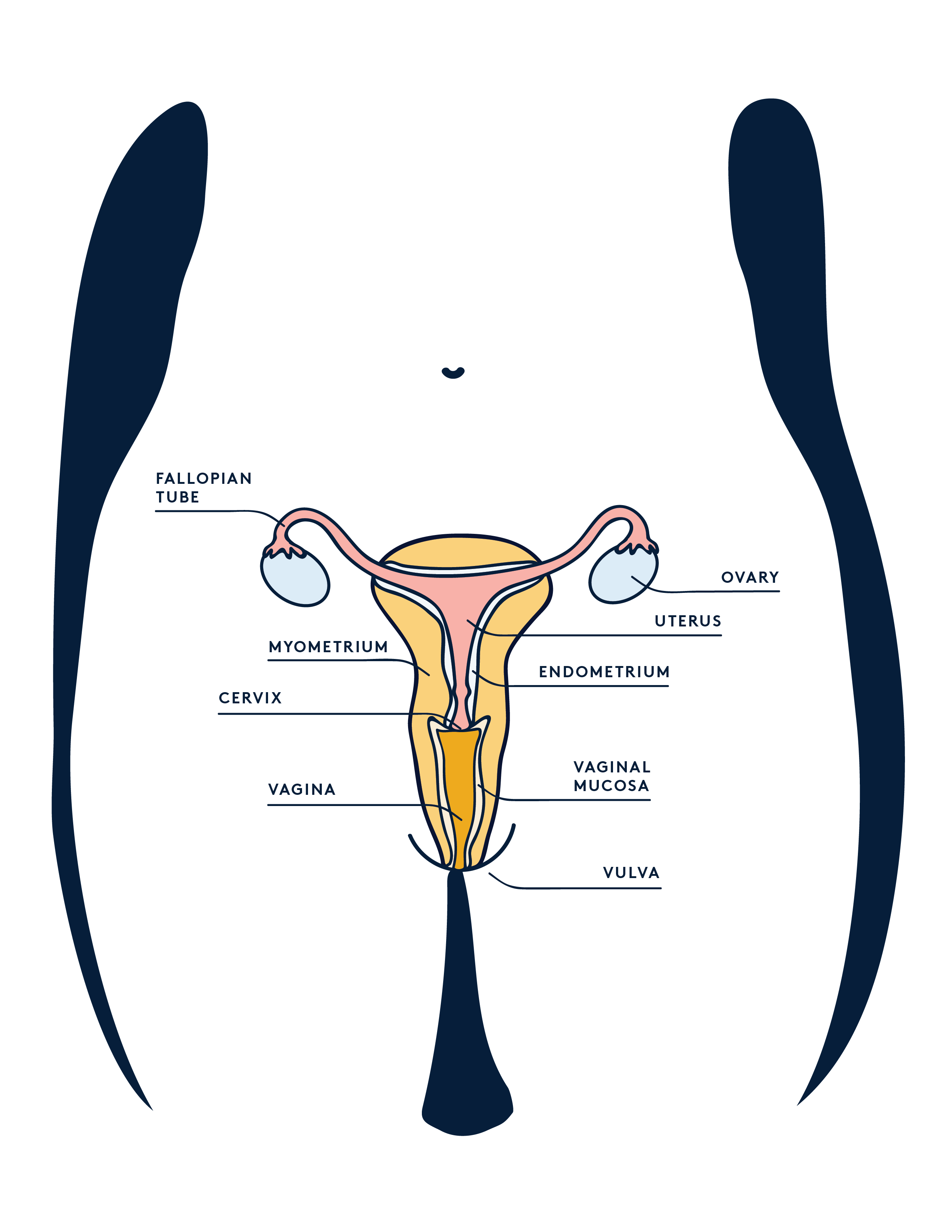

Most combined oral contraceptive pills (COCP) are taken for 21 consecutive days, followed by a 7 day break where you take a placebo pill, or no pill at all. It used to be thought that this pill-free week was mandatory, but it’s not medically necessary to bleed every month.

The COCP stops ovulation, and progesterone in it prevents the uterine lining from growing, so the bleed you have during the break is not a real period, but rather a withdrawal bleed. So why even give the option for the break? When the pill was first introduced women were accustomed bleeding every month, so the 7 day break was intended to make them feel comfortable.

The real risk of skipping the placebo week? Running out of your prescription too quickly!

Myth: taking the pill long-term makes you infertile

Another common misconception is that long-term use of the contraceptive pill will affect your fertility, and decrease your chances of conceiving.

Fertility is affected by many factors, so it’s hard to determine whether the contraceptive pill plays a definitive role, but research shows your fertility won’t be affected.

Whether you’ve been taking the COCP or mini-pill, your chances of getting pregnant within a year after coming off the pill are about the same as women who were not on hormonal contraception. A review of 17 studies found that typical pregnancy rates following discontinuation of the pill were between 79% and 96%, which is similar to those following condom use.

For 25% of The Lowdown users, their cycle returned to “normal” (ie. what they were like before the pill) within a month, 15% said 2 months, 22% said 3-6 months, and only 4% said their period adjusted within 6-12 months.

A 2002 study published in Human Reproduction even found that women who had been on the pill for more than 5 years actually conceived faster (within 12 months of discontinuing the pill) than those who were on the pill for shorter periods of time.

Age is also a large factor in fertility. If a woman goes on the pill when she’s 20, and tries to conceive after taking the pill over a decade, the fact that she’s aged is most likely the reason she’s having trouble getting pregnant.

Similarly, if someone was prescribed the pill to help with an irregular cycle, or managing a condition like PCOS, ovulation issues are likely culprits.

Myth: the pill will give you cancer

Nothing is scarier than the mention of the big C, and it often accompanies conversations on the contraceptive pill. Here’s the good news: the use of the COCP is proven to reduce the risk of ovarian, endometrial and colorectal cancer.

The bad(ish) news? Some very small studies have recorded the possibility of a slightly increased risk of breast and cervical cancer in those who have been taking the contraceptive pill for over 5 years. These findings are hard to interpret, and the evidence shows no significant association between use of COCP and mortality from breast cancer.

Scientists still don’t know whether the COCP causes this increased risk of cancer, and there’s a chance the cancers were already present, or were caused by other factors. The general medical consensus is that no, the pill won’t give you cancer.

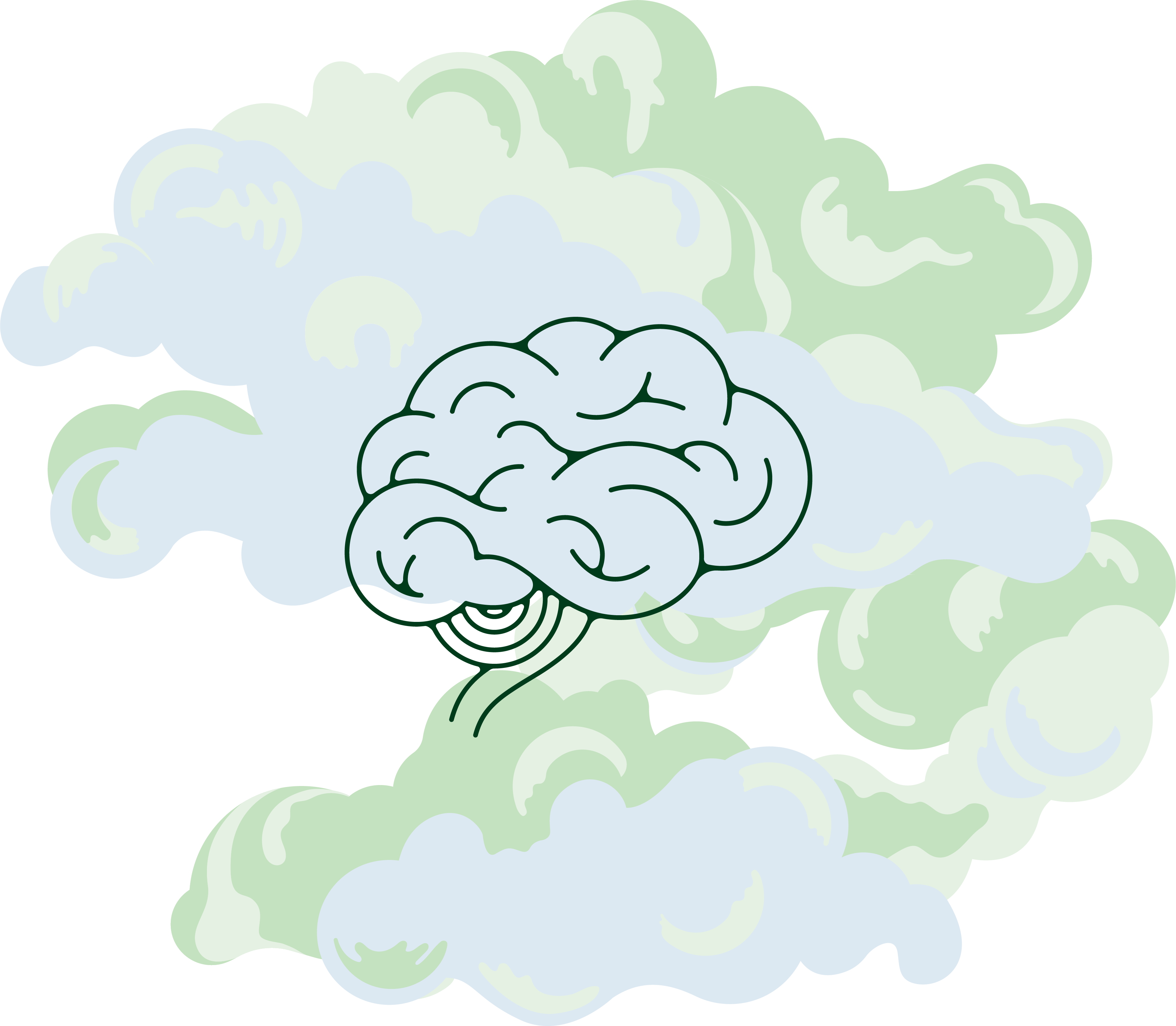

Myth: there is no link between the pill and mental health

If you mention the contraceptive pill, 99% of the time the response you’ll get is “but it causes depression!” Whether or not this is true is yet to be determined, but what is certain is that the science needs to catch up with what women are reporting.

The medical community is quick to dismiss any link between the COCP and mental health. In fact, according to the Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH)—they’re the organisation who literally write the rules on contraceptives—there is not enough research to decide whether or not the pill causes depression.

“

Science needs to catch up with what women are reporting

Their 2019 guidelines also state: “The evidence suggests that some women may experience negative mood changes when taking CHC [combined hormonal contraception]. However there is not clear, consistent evidence that CHC use causes depression; mood change is common and often related to external events.”

However, a 2016 study from the University of Copenhagen made headlines when it linked contraceptive pill use to depression. The study collected data from medical charts of both pill users and non-users in Denmark. It revealed that women who were prescribed the contraceptive pill were 23% more likely to be prescribed antidepressants at a later date. Because the study was correlative, not causative, it still didn’t establish that the pill caused depression.

This isn’t to say that the Danish study should be dismissed, and the overwhelming anecdotal proof definitely needs to be addressed. 55% of women who have left a review for the combined or progestogen-only pill on The Lowdown report that it has negatively impacted their moods and emotions—making it the most commonly reported side effect for the pill, and double the average (26%) across all methods. Pelton herself founded The Lowdown after she struggled for years to find a method of contraception that didn’t negatively impact her mood.

Research needs to pay attention to women’s experiences (which are all valid), but there is a middle ground between gaslighting women, and completely demonising the pill.

It’s also worth noting that mood swings are a common side effect of the contraceptive pill in the first 6 months, but 60% of pill users discontinue the pill after that long because of the negative side-effects. The likelihood of mood changes also depends on the pill you’re taking, as different pills contain different doses of oestrogen and progesterone.

But it’s not all bad news! The contraceptive pill could have a positive impact on your mood. In a 2003 study, 12.3% of women reported that the pill improved their mood, and 9% of women who've left a review on The Lowdown feel that the combined or progestogen-only pill had that same effect.

The pill isn’t a Tic-Tac, so it would be irresponsible to say that it doesn’t have any potential psychological side-effects––but it would be equally irresponsible to imply that it will definitely make you depressed. As with many aspects of female reproductive health, the lack of research has left women in limbo, and means finding the right pill for your body often requires trial and error.

The takeaway? We. Need. More. Research. “And for women's complaints to be taken seriously and acted upon when they present them,” adds Pelton.

“

There is a middle ground between gaslighting women, and completely demonising the pill.

Why choosing the right pill is important

Doctors use The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC) to assess whether the contraceptive pill is suitable for someone, but these recommendations don’t indicate which contraceptive pill is best (and GPs often don’t have time in a standard appointment to follow guidelines to the T). So, the criteria GP have to follow only really decide whether you can or can’t take the pill, without taking into consideration whether it’s the right pill for you.

There are 20 different formulations of COCP available in the UK (and even more pill brands), but it can be difficult to find the right one for you. Contraceptive pills vary in hormone doses and active ingredients, so your body might respond differently depending on what pill you’re taking—and what works for your mate and their mum might not work for you.

However, there are some themes that come out for different contraceptive methods and brands of pill. “Lots of women find it reassuring to come to The Lowdown to read up on how others experienced something before trying it, or to find out if their experience was the norm or the exception,” explains Pelton.

Side-effects are an unfair compromise many women have to make when choosing hormonal contraception (and some non-hormonal forms as well), but generally subside after the first 3-6 months. Often, it’s in this initial trial period that horror stories spread, and turn into myths that people take as gospel.

This isn’t to say that you should start popping the pill for sh*ts and giggles! At the end of the day it’s still a medication, and plenty of factors play a role in whether it’s the right contraceptive for your body, lifestyle and needs.

TL:DR

- There is no conclusive evidence that links contraceptive pill use with weight gain, but water retention may be an initial side effect of the pill.

- It’s not medically necessary to bleed every month and it’s perfectly safe to skip the pill-free break.

- The pill won’t lead to infertility, nor cancer.

- Research has not found substantial links between the contraceptive pill and mental illness, and any studies conducted on the topic were only correlative. However, overwhelming anecdotal evidence suggests that the scientific community needs to start listening to women’s experiences and investigate further.

Head to theldown.com to learn more about your contraceptive options—and leave a short anonymous review to help other women find the right method for them.