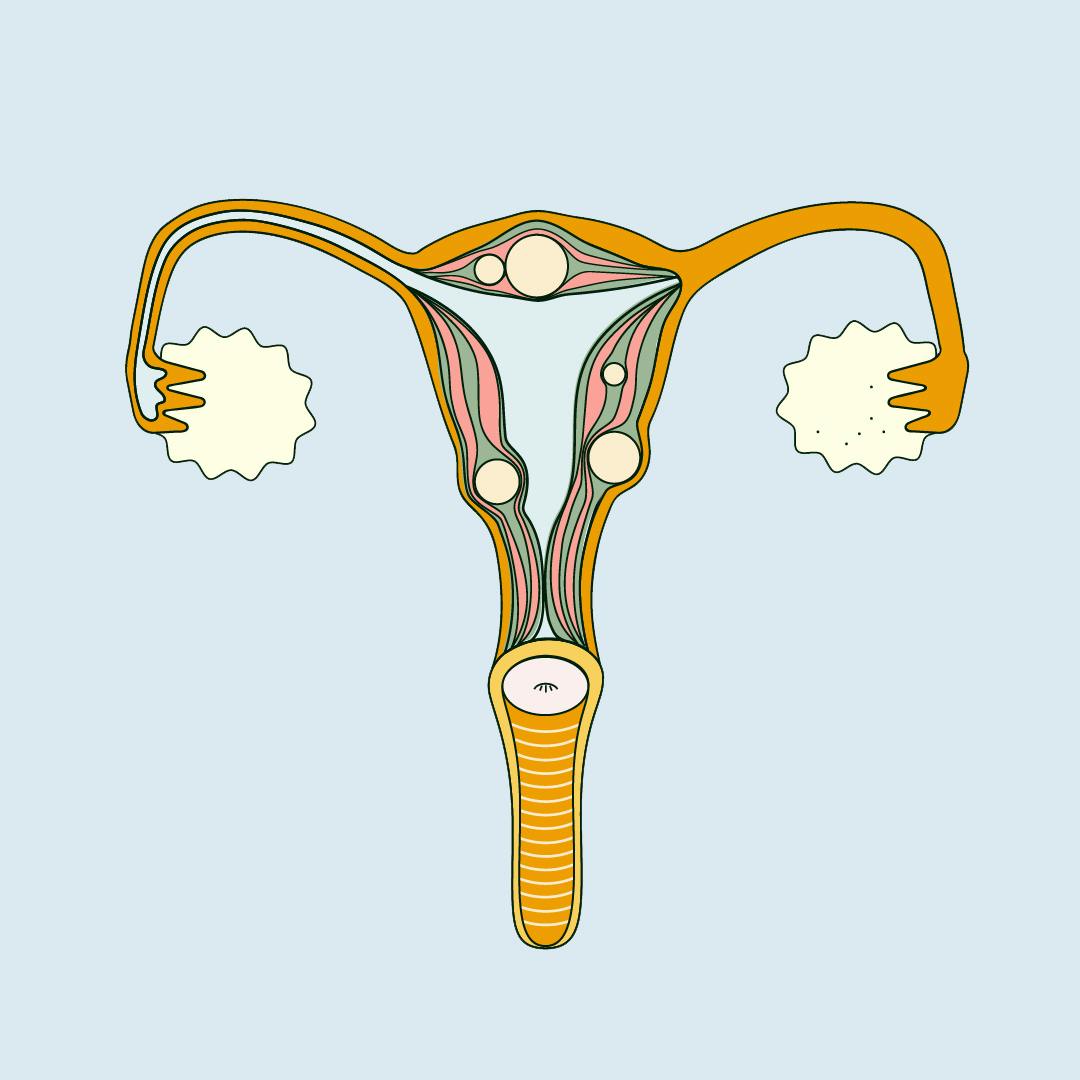

Illustrated by Sabrina Bezerra

Uterine fibroids are benign (non-cancerous) growths found in, on and around the uterus. They’re a common cause of heavy periods, pelvic pain and bleeding between periods.

Fibroids—medically referred to as uterine myomas, leiomyomas, or fibromyomas—are made up of muscle cells that multiplied too quickly, and they can vary dramatically in size.

There are 3 different types of fibroids and they can be found: inside the cavity of the uterus (submucosal fibroids), inside the muscle of the uterus (intramural fibroids), and on the outside of the uterus (subserosal fibroids). Submucosal and subserosal fibroids can also sometimes grow on a stalk (pedunculated fibroids).

There’s a misconception that fibroids can turn into cancer, however there is no proof that that can happen, and only 1 in 1000 leiomyomas are malignant.

Fibroids are pretty common, and most women will experience uterine fibroids at some point in their lives. 20-50% of women of reproductive age have fibroids, but you’re more likely to get them when you’re older.

In fact, 70-80% of women develop them by the age of 50—and yet, how many of us have even heard of them?

Symptoms and diagnosis

Even though most women will develop uterine fibroids at some point in their life, only 1 in 3 will have noticeable symptoms—the most common being heavy periods and pelvic pain.

The type and gravity of symptoms depend on the size, number and position of the fibroids. The good news is that most are harmless and usually shrink by themselves (especially after menopause), and most women don’t even know they have them. As fibroids don’t generally cause symptoms, they’re often diagnosed by chance via ultrasound during a gynaecological check-up.

However, if fibroids start to grow in size or quantity, they’re more likely to be detected and cause unpleasant symptoms that can interfere with quality of life. Some of the most common symptoms of uterine fibroids include:

- Heavy or long periods

- Pelvic pain

- Lower back pain

- Constipation, bloating, pelvic pressure, frequent urination or difficulty emptying the bladder, and pain or discomfort during intercourse (these are called “bulk symptoms” and are caused by the size and position of the fibroids)

- Difficulty getting pregnant or carrying a pregnancy to term

Uterine fibroids and pregnancy

Although fibroids aren’t known for causing infertility, in some cases they can affect fertility. Some research suggests there may be a relation between the location and size of fibroids, and the likelihood of carrying a pregnancy to term.

Submucosal fibroids (found inside the cavity of the uterus) may block sperm from entering the fallopian tubes and fertilising an egg, therefore affecting conception and the ability for an egg to implant on the uterine wall. The evidence to suggest this is tenuous, though, and most women with uterine fibroids will conceive naturally.

It was once thought that women with fibroids were at a significantly higher risk of miscarriage, but a recent 10-year study followed 5,500 women with uterine fibroids and found that the likelihood of miscarriage was the same as women without fibroids (when taking into account other risks for pregnancy loss). However, there is a risk of premature labour.

Until more research is done to establish how fibroids affect pregnancy, fibroids should be monitored in the same way as any risk factor during pregnancy should be.

Cause and risk factors

No one knows what causes the initial growth of fibroids, but we know that they’re hormonally responsive, and linked to the reproductive hormones oestrogen and progesterone.

Fibroids aren’t present before puberty, can grow rapidly when hormone levels are high (like during pregnancy), and stop growing or shrink after menopause (when your body produces less oestrogen and progesterone).

There is also a genetic component to fibroids, and women with a family history of the condition may be at higher risk of developing fibroids themselves. They are also more prevalent among women of African decent (although we don’t know why), and studies have linked obesity and fibroids (likely because fat tissue produces oestrogen).

Treatment

Unless your fibroids are causing pain or other problems, they should be monitored but they’ll likely disappear without the need for treatment.

Sometimes, however, uterine fibroids can cause painful and uncomfortable symptoms that will require treatment, or even surgery. Treatment for fibroids is not a one-size-fits-all approach, and depends on the placement, size, and number of growths present.

Medications

Medications can’t cure fibroids, but they can shrink them and help manage symptoms. If you’re trying to manage heavy periods caused by fibroids, your doctor may prescribe you certain forms of hormonal contraception (for example, the IUS, which has shown to reduce menstrual bleeding or even stop periods altogether). If contraception isn’t desired, a non-hormonal medication called tranexamic acid is often prescribed and reduces blood loss by 40%.

Other forms of hormonal medication can also be prescribed to reduce the size of fibroids, such as Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) analogues, which stop the production of both progesterone and oestrogen.

Another common type of medication used to shrink fibroids is ulipristal acetate, but in February 2018 the Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) warned that it was under EU safety review after several women reported serious liver damage while taking the ulipristal acetate medication Esmya. Liver damage was only reported in rare cases, but the MHRA established that it should not be prescribed to new patients, and that liver function should be monitored once a month for women already on it.

Surgery

What surgery is carried out largely depends on the size and type of fibroids.

- Hysteroscopic resection and morcellation: Submucosal fibroids can be removed via hysteroscopic resection, which is a minimally invasive procedure and doesn’t require any incisions. A thin telescope and surgical tools are inserted through the cervix several times to remove the fibroid tissue, and can often be performed under local anaesthetic. A new and improved version of hysteroscopic resection is hysteroscopic morcellation, which only requires one insertion (as opposed to several). However, since the technique is so recent, there is little evidence on its safety and long-term effectiveness.

- Myomectomy: a myomectomy surgically removes fibroids from the wall of your uterus, either through a small keyhole incision on your tummy, or through open surgery. Myomectomies aren’t suitable for all types of fibroids, but they’re usually an effective treatment.

None of these procedures guarantee that fibroids won’t return.

- Hysterectomy: In more severe cases, a hysterectomy is performed. This is the only treatment for uterine fibroids which completely cures fibroids, but it also means you won’t be able to get pregnant. Hysterectomy is a very invasive surgery and is typically only recommended for those who have very large fibroids, are close to (or have gone through) menopause, or are certain they don’t want to get pregnant.

Non-surgical procedures

Aside from traditional surgery, treatment for uterine fibroids also includes non-surgical procedures. These include uterine artery embolisation and endometrial ablation, which sound frightening but simply involve cutting off the blood supply to fibroids by blocking blood vessels in the uterus, causing the fibroids to shrink.

Newer techniques include MRI-guided procedures, which use sound waves to destroy fibroids. The long term benefits and risks of these techniques are still unknown, and the procedure isn’t yet widely available in the UK.

TL;DR

- Uterine fibroids are benign growths that grow inside the cavity of the uterus (submucosal fibroids), inside the muscle of the uterus (intramural fibroids), and on the outside of the uterus (subserosal fibroids).

- Fibroids are extremely common, but most of the time they're asymptomatic and women don't even realise they have them.

- Only 1 in 1000 fibroids are diagnosed as cancerous.

- Fibroids are a common cause of heavy, painful periods.

- Fibroids can sometimes affect fertility, but more research needs to be done in this area.