Written by Beccy Hill

Illustrated by Erin Rommel

Period pain has existed since the beginning of time, but despite the fact that it affects 9 out of 10 women in the UK, the condition is largely dismissed by the medical and scientific community. As women, we’ve coped with dysmenorrhea, as a birth right of sorts. To quote Kristin Scott Thomas in Fleabag: “Women are born with pain built in.” It’s like a subscription service you never signed up for, and can’t unsubscribe from.

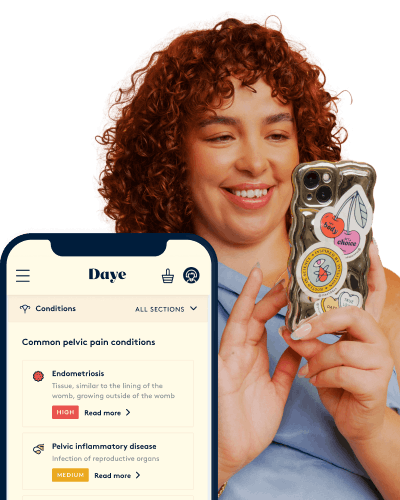

Take the pain out of your period

90% of us experience period pain, and when left unmanaged it leads to us losing 150 million productive work days per year.

Well, we’re saying time’s up. Time’s up on the lack of scientific innovation and research on menstrual cramps, PMS, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and other ovarian, vaginal, or uterine health conditions, because period pain is a universal health condition.

This was confirmed in 2016, when John Guillebaud, professor of reproductive health at University College London, revealed that period pain can be as “bad as having a heart attack”. A. Heart. Attack. He continued to say “Men don’t get it and it hasn’t been given the centrality it should have. I do believe it’s something that should be taken care of, like anything else in medicine.” A little louder for those at the back please, John. The lack of research on period pain is not only due to centuries worth of deeply ingrained sexism, but also the shame and stigma attached to menstruation. If the conversation is kept in the dark, then that’s where the problems will stay. So how does this affect the everyday lives of women across the globe, not just physically but also mentally within the attitudes of different societies?

“

Sometimes it feels like there’s a pole up my bum.

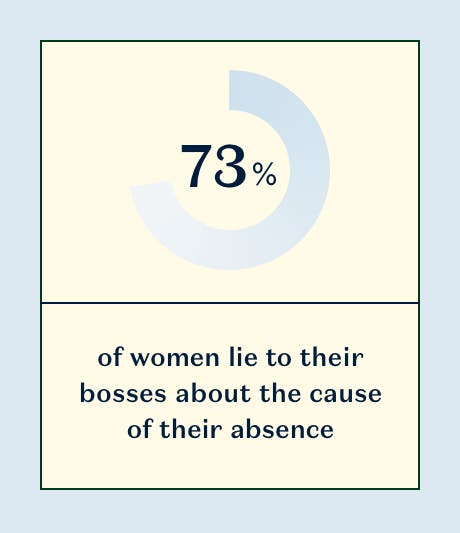

“Sometimes it feels like there’s a pole up my bum. I get the sweats and can’t move, and I have to take a day off work so I can just lie there and cry.” This is how Wendy Lathwell, a 28-year-old charity worker from London, describes her monthly period pain. When I ask if she is honest with her employer about why she can’t make it into the office, she replies “No, I have to make up some bullshit excuse because it’s too awkward.” It’s clear that she is not alone. In 2017, a survey conducted by Wear White Again reported that period pains are responsible for 5 million sick days per year in the UK, with 73% of women lying to their bosses about the cause of their absence. The stigma surrounding periods is undeniably decreasing thanks to advancements in the mass media, like Bodyform daring to use red liquid instead of blue in their advertisements for sanitary pads (which seems crazy to applaud, but we have to take the wins as they come) and the #FreePeriods movement evolving from an online campaign into an IRL protest outside the Houses Of Parliament in December 2017. However, at ground level, for the everyday woman, it’s clear that the shame is still a very heavy burden to bare.

Following Netflix’s Oscar win for Period. End of a Sentence, the BBC Four radio show Woman’s Hour invited 3 women from the British Asian community to discuss their experience with attitudes to periods. Sonar Sashdal Patel describes menstruating as a rather low-key matter in her Hindu household, until she found out she wasn’t allowed to attend certain religious events. “There are certain goddesses where if women have their period, they aren’t allowed to go,” she says. “We abided by that. We weren’t an extreme family…we didn’t do it in our own home but when it happened outside of our home, we respected what other elders in the community thought and we didn’t go.”

In September of last year, the Indian Supreme Court ruled to end a ban that kept women of menstruating age from entering the Hindu temple of Sabarimala in Kerala. Prior to that, women and girls aged 10-50 (aforementioned menstruating age) were prohibited from worshiping in the temple as it was thought that they were impure. Despite Hindu scriptures not explicitly outlining the exclusion of women as a necessary religious practice, many traditionalists reacted strongly against the new order.

“

[In the UK] 137,000 children have missed school because of period pain.

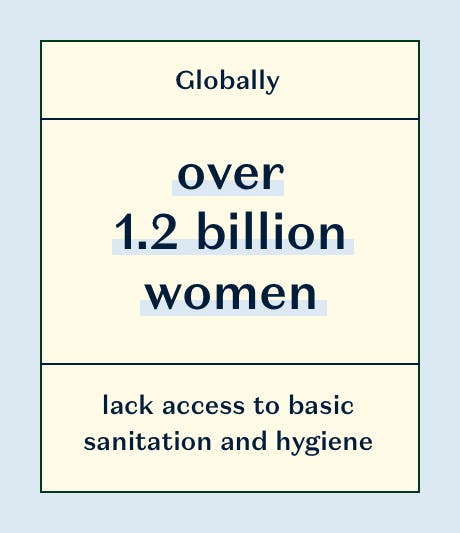

A Unesco report estimates that 1 in 10 girls in Sub-Saharan Africa will miss school during their menstrual cycle, this equals as much as 20% of a given school year. The reasons for this are varied, but a lack of access to information, adequate facilities and sanitary products are undeniable. It’s important to highlight that this situation isn’t limited to developing countries. Period poverty is a very real problem in the UK too, where 137,000 children have missed school because of it and 1 in 10 girls can’t afford period products. Globally, over 1.2 billion women lack access to basic sanitation and hygiene, and the United Nations has recognised menstrual hygiene as a global public health and human-rights issue.

In 2016, when Olympic swimmer Fu Yuanhi announced she was on her period in a post-race interview, she was celebrated as a feminist hero in the Western press. However, in her native China, the reactions were somewhat different. Weibo, a popular Chinese micro-blogging site, saw users querying how Fu hadn’t managed to turn the pool red. Tampons are extremely rare in China, with user statistics from the time of her race being as low as 2%. This is due to a general belief that tampons are not good for female health, and that they will break the hymen and rob girls of their virginity. This taboo runs so deep that in 2015, not a single tampon was manufactured in China, but 85 billion pads were produced in the country.

“

Women are excluded from communities for simply daring to menstruate.

When you introduce the idea of dysmenorrhoea on top of these existing cultural and logistical problems, it’s disturbing how much periods are setting back the lives of women and girls alike. It’s difficult to research the effects of period pain exclusively because we have not yet reached the stage of having open conversations about periods in general. When women are excluded from communities for simply daring to menstruate, how can they then be open about how much pain they are in? When girls cannot afford sanitary products and are using anything they can find to absorb the blood, regardless of sterilisation, how can we introduce the idea that there are ways to combat the pain they are also undoubtedly experiencing? And if we would rather call into work and say we’re sick than explain we have crippling menstrual cramps, how can any concrete research on the severity and spread of the problem be collected?

“

We must be repeatedly open about our periods and our experiences and force the powers that be to listen.

Ultimately, the taboo around every single aspect of menstruation is what is preventing societal change, including medical developments and research into period pain. This is why we must be repeatedly open about our periods and our experiences and force the powers that be to listen. Thanks to the amazing work of Amika George (founder of the #FreePeriods movement mentioned earlier) in March 2019 the UK government announced sanitary products would be free in secondary schools across the country. The phrase ‘respect our existence, or expect our resistance’ never felt more appropriate.