Illustrated by Erin Rommel

Over the past few years there’s been a lot of awareness around the gender pay gap, highlighting how gender can affect how much we earn, our likelihood of being hired, promoted, or even just being taken seriously in a meeting.

But that same gender discrimination affects the quality of medical attention we receive, and we’re only now staring to speak up about it.

Female pain has historically been sidelined and dismissed (this is especially true for Black women and WOC) by the medical community, and it’s often written off as a normal part of womanhood.

If you’ve ever had to deal with reproductive health issues, painful periods, or contraceptive side effects, you can relate to the frustration of not being taken seriously by doctors.

Centuries of unconscious bias and a lack of research has created a phenomenon where women are often neglected, misdiagnosed or prescribed the wrong treatment. It’s the sort of gender bias that is so ingrained in society that it often goes unchecked. So what do we do when we turn to medical research for answers, and get greeted with a shrug?

A brief history of the gender pain gap

To truly understand how the gender pain gap became the public health crisis it is today, we need to rewind back a few thousand years.

Since Ancient Greece, the female body was considered “inferior” to the male body. The philosopher and scientist Aristotle once said that women are a “deformed male; and the menstrual discharge is semen, though in an impure condition.”

To this day, many anatomy books still use the male body as a standard, and even as recently as the 20th century, medical researchers thought that women were just “little men”—so that whatever worked for a man would work for a woman.

In the Victorian era women’s illnesses were said to be the result of “hysteria” and women were institutionalised rather than treated. This sort of practice happens today, where we’re told our pain is merely perceived, or “all in our head”. To this day we are more likely to be prescribed sedatives instead of pain relief because we’re seen as being more anxious (read: emotional), and we’re more likely to be written off as psychiatric patients.

It all starts with clinical trials

Women have also historically been excluded from medical research. Until the 1990s, researchers banned women of childbearing age from participating in clinical trials in the US, Europe and Canada.

This was partly a safety measure as a result of the 1950’s thalidomide disaster, where pregnant women were prescribed thalidomide to treat morning sickness, unknowingly causing thousands of birth defects.

It was also believed that the hormonal fluctuations from the menstrual cycle would “pollute” medical data in trials and make the research more expensive.

At the foundations of the gender pain gap is the fact the medical community knows way less about the female body than they do about the male body.

The fact that a 70kg white male has been the model used in clinical trials for decades led to a huge body of medical evidence based entirely on the male physiology, so researchers don’t truly know how women metabolise and react to many medicines, nor how they experience or manifest pain.

The efficacy, dosage and side-effects of many drugs (including over-the-counter painkillers like ibuprofen) were never tested on women.

When the FDA lifted its ban on women participating in clinical trials and introduced the “Guideline for the Study and Evaluation of Gender Differences in the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs” in 1993, researchers pointed out that because studies on aspirin in heart disease and stroke only included men, so scientific community was unsure whether aspirin was actually effective in women with those indications.

As recently as 2013 the FDA had to reduce the doses of the sleeping pill Ambien for women by half, after a class action lawsuit against the pharmaceutical company Sanofi by Ambien users who complained of sleep-driving while under the drug's influence.

After the FDA launched an investigation, it was found that women were, in fact, more susceptible to being impaired because they eliminate the drug from their bodies more slowly than men.

Formulations should be tailored

Very little research has looked into how the female anatomy or the menstrual cycle can affect the way women experience or present pain, and whether different medications work better on our bodies.

Researchers are still figuring out the scope of the issue, but they’re slowly beginning to understand how women disproportionately experience adverse side effects of medications. A US Government study found that 8 in 10 of the drugs pulled from the market between 1997 and 2000 posed a bigger health risk to women.

So, why haven’t drugs been tailored to the female physiology? The answer may be mice. Drug development begins with animal trials, and until recently almost all initial research used only male mice. A 2015 review found that 79% of pain studies used only male mice, potentially sabotaging further research.

Even the researchers conducting the trials have mostly been men. A 2017 study found that 1.5 million (!!!) medical papers revealed a link between the author's gender and the likelihood of gender and sex being taken into consideration during the trial. The study found that not including female researchers could have “potentially life-threatening and costly consequences”.

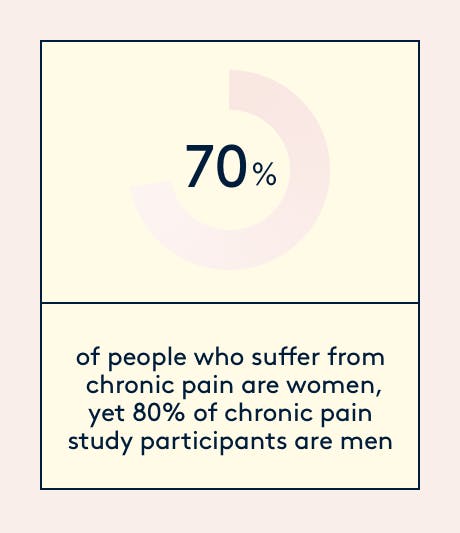

In the case of chronic pain, 80% of study participants are male even though 70% of those affected by chronic pain are women, who usually tend to feel it more often and more intensely than men. Take endometriosis, for example. The condition affects 1 in 10 women, costs the UK economy £2.4 billion annually, yet it takes 7.5 years on average to diagnose.

The treatment gap

Aside from being excluded from medical research, the biggest symptom of the gender pain gap is the quality and level of medical treatment women receive. Countless studies and surveys show that female health issues are routinely taken less seriously than men’s, even when they’re of the same severity.

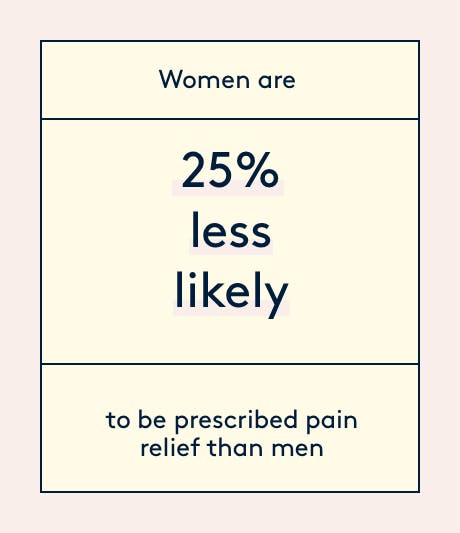

When women show up to A&E with abdominal pain, they wait on average 65 minutes while men only wait 49. Women are also 25% less likely to be prescribed pain relief than men.

A 2016 study also found that women are on average 50% more likely to be misdiagnosed when they have a heart attack, because women present symptoms that differ from men’s when having a heart attack but doctors fail to recognise this—a phenomenon known as “Yentl syndrome”, where women are often misdiagnosed, dismissed, or told their pain is just perceived.

For women of colour the situation is even bleaker. Black African women were least likely to receive pain relief during labour, and are also 5 times more likely to die of childbirth than white women.

Where are we now?

Although the gender pain gap is far from being shut, our voices are starting to be heard. In 2015 the National Institute of Health (NIH) in the US introduced a policy requiring medical researchers to take sex into account as a biologicable variable. Similarly, in 2017 the NHS issued a dictatum that doctors must “listen to women” to improve the state of endometriosis diagnosis (better than nothing…).

No legislation has been put into place to help close the gender pain gap, but it’s a start.

TL;DR

- Women were banned from clinical trials until 1993, and the male physiology has been used as a standard to test drug effectiveness and safety. Most over-the-counter painkillers have never been tested on women.

- Little to no research has been done on how the menstrual cycle and female anatomy affects the way we metabolise and react to drugs.

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, and yet diagnostic criteria are based on the symptoms typically experienced by men, leaving women 50% more likely to be misdiagnosed.

- Women are more likely to be prescribed sedatives, rather than painkillers, because our pain is dismissed as perceived.

We’re on a mission to close the gender gap in medical research & innovation, starting with menstrual pain. As a token of acknowledgement that the gender pain gap has existed for far too long, we started #MindThePainGap. When you refer a friend to Daye, they get £5 off their first box and you get £5 off your next box.