Written by Izzie Price

Medically reviewed by Sarah Montagu (RN DFSRH, BSc)

Illustrated by Erin Rommel Sabrina Bezerra Maria Papazova

When was the last time you inserted a tampon into your vagina before grabbing your water bottle and heading to the gym?

When was the last time you gently pressed a menstrual pad into your underwear in the work toilet cubicle before making your way back to your desk?

When was the last time you hoisted a pair of period underwear into place before crawling into bed with a hot water bottle?

When we’re on our periods, we utilise menstrual products during countless quotidian moments of our lives. We put them in place without thinking; because they’re functional, right? They’re there to serve a very basic purpose that, at its heart, allows us to continue on with our lives as normal while we’re menstruating (period pain notwithstanding).

And so, whenever it was that you last inserted a period care product – whether it was this morning, last week or last month – I’m prepared to bet good money that you didn’t consider the chemicals that could (could!) be present in said product.

I’m not judging you. Before I started working on this article, I’d never given the chemicals present in period products a second thought. I didn’t even know it was a thing – but it is, and it needs addressing.

So, while it slightly chills the depths of my bones to do this research (as a 30-year-old woman with hypochondriac tendencies who’s been using a variety of menstrual products once a month for around 17 years), we’ve put together an article that calls attention to what could be going on in our period products; why it matters; and what needs to be done about it, both on a personal level and in terms of much wider public health initiatives.

So there are chemicals in our period care products. So what?

It’s a fair question. After all, we only use period care products for a few days once a month, right? And that’s not even counting pre-puberty and menopause/post-menopause.

Sorry, team; it turns out that the average menstruater will use around 11,000 tampons or sanitary pads in their ‘period lifetime’ – which can be as long as 40 years.

Yep, it’s a lot. When you factor in tampons, pads, washes, sprays, powders and wipes (collectively known as feminine hygiene products, or FHPs), these products are used pretty widely across the world – US sales alone of these products are over $3 billion annually.

And their level of regulation is…not great. While feminine health products are considered ‘medical devices’ by the US FDA, they are not considered as such in Europe and the UK, and across all geographies there are few regulations that ask brands to disclose specifics when it comes to their composition.

So…what exactly can be in period care products?

Ok, let’s get down to it. One review found that the following chemicals can be present in menstrual products:

- Phthalates

- Volatile organic compounds (VOCs)

- Parabens

- Environmental phenols

- Fragrance chemicals

- Dioxins

- Dioxin-like chemicals

That’s a hell of a lot of stuff – so let’s break some of this down.

A range of them, including phthalates, phenols and parabens, can also be described as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs); and this is an issue of concern (more on this a couple of sections down).

Another common type of EDC is PFAs, which stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances – also known as ‘forever chemicals’, which are man-made compounds that could gather in the body over time.

A recent Washington Post article called attention to new research which found that PFAs can be present in ‘the lining of period underwear, the wrappers of tampons and in other menstruation products’. The research was conducted by the University of Notre Dame, which studied over 120 different types of menstruation products (including cups, pads, underwear and tampons) sold in the US.

PFAs weren’t found in all of them, but they were found in some; and, while not giving specifics, the study noted that “a good fraction” of the period underwear products contained detectable levels of PFAs in the lining. Meanwhile, no tampons were found to contain PFAs; but forever chemicals were found in some tampon wrappers and applicators, together with liners and incontinence pads.

And then there are VOCs, as mentioned in the initial list above. In relation to menstrual products, one survey which studied VOCs in feminine hygiene products sold in the US market described VOCs as: ‘components of [feminine hygiene products – which the survey defined as including ‘washes, tampons, menstrual pads, wipes, sprays, powders and moisturizers’] that are added as fragrances, adsorbents, moisture barriers, adhesives and binders,’ and that ‘may also be inadvertent in the raw materials or packaging’.

‘Examples of notable VOCs include benzene, a known carcinogen, 1,4-dioxane, a likely carcinogen, and naphthalene, a possible carcinogen’, the survey continued.

How are these chemicals absorbed into the body?

Well, that’s part of the concern – because vulvar and vaginal tissue is extremely permeable and sensitive, with high uptake rates of chemicals.

The aforementioned VOC survey explains it pretty succinctly: ‘The permeability is a result of the structure, occlusion, hydration and susceptibility to friction of vaginal and vulvar tissues. Arteries, blood vessels and lymphatic vessels are abundant in the vaginal wall, which allows for the direct transfer of chemicals to the blood through peripheral circulation.’

So…why are these chemicals a problem?

Another fair question.

Let’s start with EDCs. The endocrine system is effectively the hormone system; and it comprises hormones (obviously), organs and glands. Hormones are, as you’re no doubt aware, responsible for a vast range of bodily processes from reproductive development and metabolism to insulin production and blood pressure.

EDCs basically cause problems for the hormonal system. As ChemTrust puts it: ‘Some [EDCs] change the amount of hormones in our blood; others change our sensitivity to hormones; other EDCs block hormones from doing their job; and others even mimic the body’s natural hormones.’ And ChemTrust goes on to point out that the longer-term health ramifications of EDCs interfering with the hormonal system can include:

- Infertility and reproductive problems

- Endometriosis

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Heart disease

- Breast cancer

When it comes to PFAs specifically, they’ve been implicated in various severe health effects – like disruption of the endocrine system, which is unsurprising, but also some cancers, high blood pressure and developmental problems in children.

And what about VOCs?

Well, the survey that explored VOCs in feminine hygiene products sold in the US noted that ‘exposure to high concentrations or long-term exposure of VOCs has been associated with many known or suspected effects including irritation to eyes, skin and nose; damage to the respiratory system, liver and kidney; reproductive effects; and carcinogenicity’.

The survey tested 79 feminine hygiene products and found that all 79 tested products contained multiple VOCs; but generally at low concentrations. ‘Using conservative but realistic exposure assumptions, the use of FHPs is associated with calculated cancer and non-cancer risks that fall below protective health guidelines in most cases’, the survey reads; but it adds: ‘However, several menstrual pads, washes, sprays and powders with higher levels of toxic VOCs, including benzene, n-heptane and 1,4dioxane, can be associated with calculated risks that approach or exceed guidelines, and simultaneous use of several FHPs will increase risk levels’.

And this systemic review found, ‘All studies that tested for chemicals in menstrual products found them’; and, when reviewing a select five studies, found that tampons had ‘the highest total target of VOCs’. Finally, while we’re talking about the harm potentially caused by our period care products, we should also mention sanitary pad dermatitis, as mentioned in one article, which has been found to present as an ‘itching and burning sensation over [the] perineal area at the contact site with a sanitary pad’. In terms of how and why a sanitary pad could cause this reaction, the author of the aforementioned article concluded that ‘the material used for the manufacture of sanitary pads is expected to be the main allergen’.

So, what can we do about it?

Well, for a start, the issue needs far more attention and urgency from a public health perspective.

One aforementioned review noted a major research gap, including a worrying lack of studies on comparatively newer menstrual products like period underwear and cups or discs: ‘In addition to measuring chemicals in these products, future research should focus on clarifying the exposure per menstrual cycle to these chemicals to understand how menorrhagia and cycle length influence exposure from menstrual products.’

The VOC survey, meanwhile, urges more transparency on the part of manufacturers: ‘Product labels were not informative with respect to VOC composition and concentration. We recommend disclosure of ingredients and production dates and suggest the removal of VOCs that do not serve functional or aesthetic purposes.’

You’ll (hopefully) be relieved to know, though, that you don’t need to rely entirely on researchers and manufacturers to start eliminating potential EDCs and VOCs from your life – there are steps you can take, too.

For example, ChemTrust suggests opting for organic cotton tampons and pads where you can – emphasising that you should look for an organic certification logo – together with silicone menstrual cups and reusable fabric pads. ChemTrust also encourages you to choose unscented products, and to select products marked “Totally Chlorine Free (TCF)”.

‘Some products are bleached with chlorine,’ ChemTrust explains. ‘Dioxins [as mentioned above] are a by-product of this bleaching. They can interfere with the hormone system, and have been linked to reproductive and developmental problems. By opting for TCF products you are less likely to be exposed to harmful dioxins.’

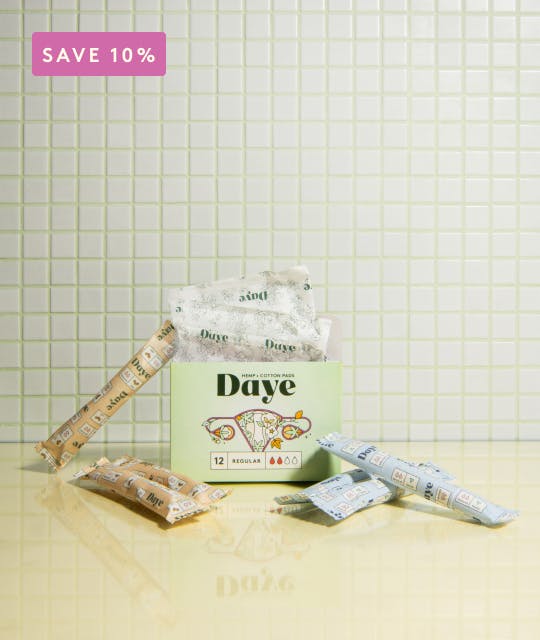

And speaking of organic period care products – look no further than Daye Tampons.

Organic and fully sustainable, they’re made with 100% organic cotton and don’t contain any plastic. Plus, they come in applicators made from renewable sugarcane. They meet strict safety standards, have been sanitised with gamma rays to remove any contaminants that could cause TSS and infections; and they have a protective sleeve that stops fibres shedding inside the vagina.

Above all, remember: You have a right to know what’s in your menstrual products – or in any products that you’re using in your everyday life, especially those that are coming into contact with your body.

As Women’s Voices says: ‘Improved ingredient disclosure which could indicate the presence or absence of chemicals of concern would aid in making informed choices of period products’ – because ‘it is reasonable to want to know about the presence (or absence) of a reproductive toxin, carcinogen, irritant or allergen in a tampon’.

Amen to that.

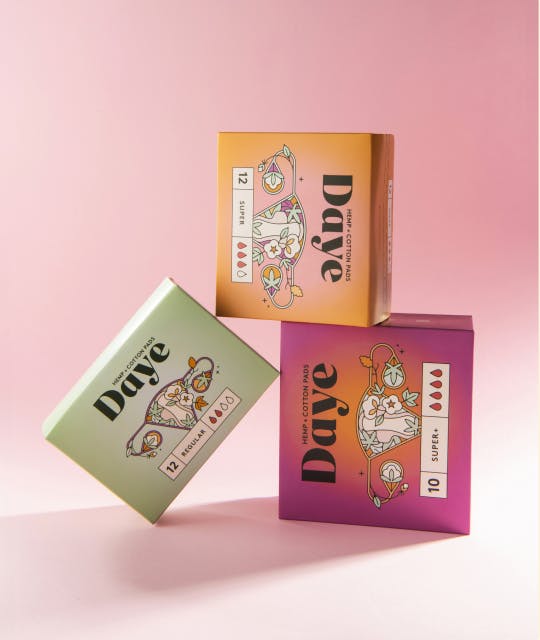

Relevant products